This article first appeared in Fourth View’s Take Note Of newsletter on July 24, 2020. Sign up to have weekly insights and explainers delivered to your inbox.

All of this money must lead to inflation, right?

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was the largest economic stimulus package in the country’s history at $2.2 trillion, or nearly 10% of GDP. The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has expanded by roughly $3 trillion since the beginning of the year as they started purchasing corporate bonds and corporate bond funds. With millions of people and businesses suddenly receiving “money for nothing,” surely it will raise prices and contribute to inflation, right?

The fiscal and monetary stimulus that has flooded over $5 trillion and counting into the economy sets up a debate not just about the nature of inflation but about something called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), if not in name but in practice. In short, supporters of MMT argue that government deficits should not be a constraint on spending given the government’s ability to print money, and the act of the government increasing the money supply is not inflationary, provided the economy is not at full employment and taxes are sufficiently high.

Up until this point, support for MMT has been confined to the far left wing of progressive politics, with the likes of Keynesian economist Paul Krugman and Obama-era Treasury Secretary Larry Summers arguing against it. Conservatives have warned about the dangers of inflation in theory, but in practice many have been willing to support debt-financed spending and tax cuts. But in the latest round of stimulus, perhaps we’ve found a spending program both sides of the aisle can get behind.

How much money have we pumped in the system?

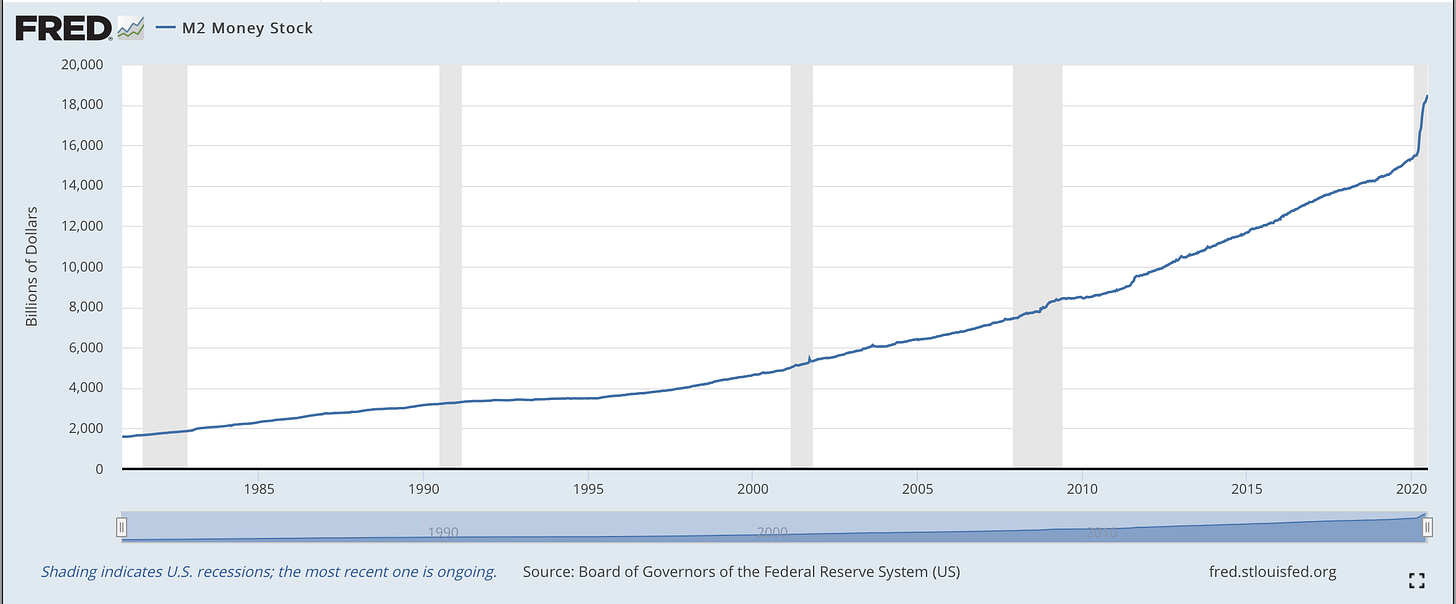

Since the beginning of the year, M2 (the measurement of all the cash and near-cash deposits in the banking system including checking accounts, savings accounts, and money market accounts, for example) has increased from $15.3 billion to $18.4 billion. A 20% increase in half a year has never been seen. Many left-leaning economists will point out that a rise in M2 does not directly cause an increase in inflation; right-leaning economists contend they are rarely out of lockstep. Don’t expect a resolution anytime soon – they’re still debating whether the expanded monetary and fiscal policy of the 1930s caused or exacerbated the depression.

So why haven’t we seen inflation?

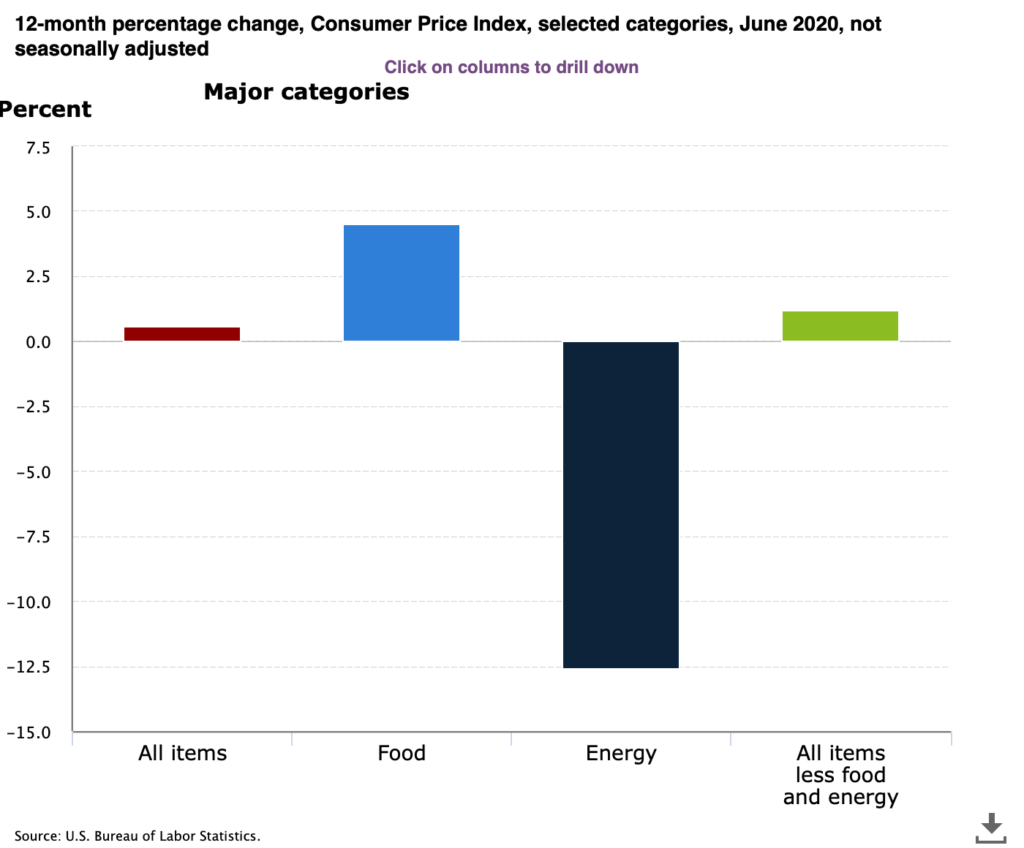

Luckily, we don’t need to resolve this philosophical argument to understand the current state of inflation. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which measures the Consumer Price Index, energy prices have declined by 12.5% over the past year. Gasoline prices alone dropped by over 23%. This has nearly canceled out the impacts of rising food, healthcare, and education costs over the same period leaving us with a very modest 0.6% inflation reading.

What does this mean going forward?

Gasoline and natural gas prices are arguably the most volatile components of inflation, so when a recession hits their decrease is able to mitigate spikes that elsewhere. In both the 2008 and current recessions, this provided politicians with the perfect cover to increase debt-fueled fiscal and monetary stimulus packages. It seems like a win-win situation.

What would happen if gasoline and natural gas prices didn’t decline? Let’s rephrase that – what would happen if we didn’t have the benefit of gasoline and natural gas price declines? What if we relied on electric vehicles, or renewable energy sources that had more stable prices? Or what if our use was simply more efficient and was thus not as large of a component in household budgets as food? Ironically, the same advocates for MMT are also advocating for the elimination of the energy categories which have provided cover for the healthcare, food, and educational inflation which has been far more steady and constant over the past decade.

For the time being, it seems we can pursue massive government stimulus without paying the price…but for how long? A recession 10 years from now may not afford us the same courtesy.

If you enjoyed this note, check out prior newsletters from Take Note Of.