Despite staying out of the headlines for the past several weeks, the prospect of a trade deal with China remains on the minds of investors, international relations professionals, and political observers around the world. While a deal in the near future remains likely, many have taken a more measured view that the agreement is a step towards improved economic relations rather than a panacea. Let’s take a step back – what have we learned from the trade deal?

Tarrifs Don’t Work

Marika Heller – Albright Stonebridge Group

The trade war and U.S. tariffs on roughly $250 billion worth of Chinese imports into the United States have not addressed the critical unfair trade practices that affect U.S. businesses, and instead have cost Americans $3 billion in extra taxes and $1.4 billion in lost economic efficiency each month. Annually the United States will lose $40 billion in exports to China due to China’s retaliatory tariffs. While these costs are minimal for a $19 trillion economy, they are completely unnecessary as the tariffs have not been effective leverage against China based on China’s shrinking reliance on export growth, and the expected outcomes of the U.S.-China bilateral trade negotiations. The U.S. export market is simply not large enough to force China to yield to U.S. demands that would end industrial policies Beijing perceives as essential to China’s economic development, and China is becoming structurally less reliant on exports as it shifts to a consumption-driven growth model, with exports consisting of only 20% of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016 compared to 36% in 2006.

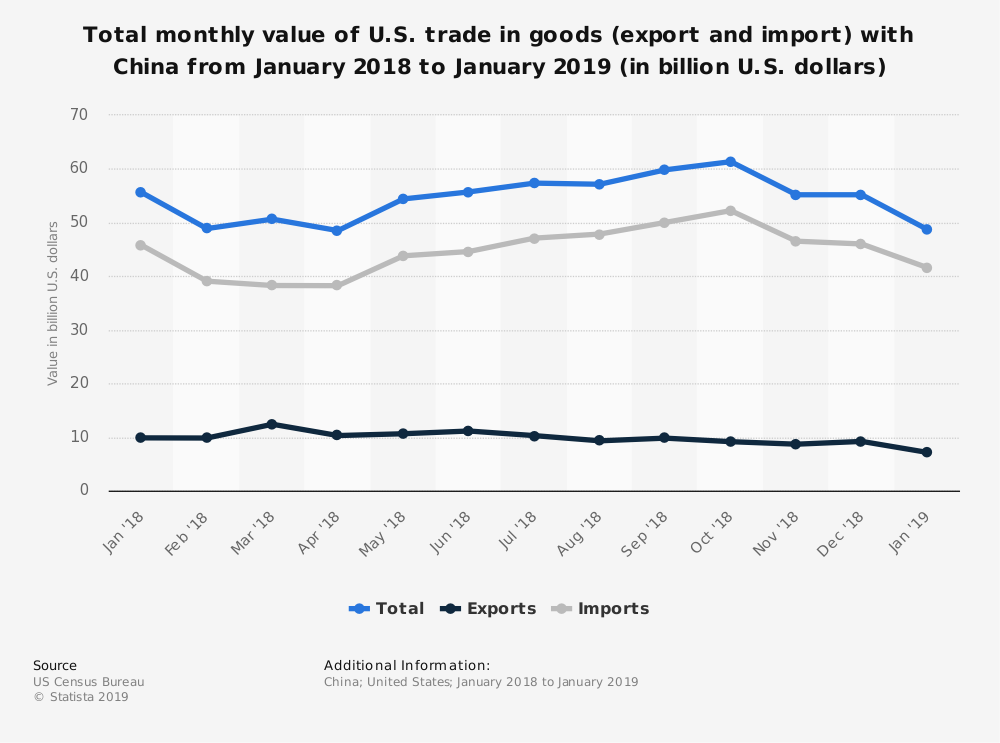

In addition, the current U.S.-China trade agreement framework appears to rest on $1 trillion in agreed annual purchases from China of U.S. goods, including an extra $30 billion in U.S. agricultural imports. While this may help rebalance the trade deficit between China and the United States, a priority of President Trump, the trade balance itself is a faulty concept that is an inadequate measure of the overall health of the trade relationship. In addition, if alleviating the trade deficit is the administration’s top priority, then the tariffs themselves have failed to do even this as the trade deficit with China increased by $43.6 billion in 2018 according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. Moreover, the trade agreements reportedly being drafted on important structural issues impacting U.S. businesses such as technology transfer, intellectual property, and industrial subsidies, are expected to be relatively superficial documents designed to allow President Trump to declare victory, and China is not expected to agree to the substantive enforcement mechanisms necessary to enact structural changes to their economy that would make it more fair for U.S. companies to participate and compete in China’s market.

Trade War Was Justified

Bryan Cosby – Fourth View Contributor

After decades of widespread mistreatment and under the new leadership of a populist president, the U.S. has grown tired of China’s unfair trade practices. Stated grievances include: the theft of hundreds of billions of dollars in U.S. intellectual property, economic espionage, forced technology transfers, asymmetrical import taxation, and lack of enforcement of international patent law. It is the view of President Trump that China has grown rich from decades of an unfair trade relationship at the expense of the U.S.. As two of the most powerful global economies, trade between both countries is inevitable. President Trump has argued that the U.S. must make sure that the basis of our trade is fair for both sides.

As China has consistently made clear, it will not bow to the demands of international trade organizations or other nations. That is why the US strategy must force China’s hand so that they have no choice but to change their trade practices. At a time when the Chinese economic growth miracle has just begun to slow, great trade pressure carries more weight than ever before. While the large trade deficit that exists between the US and China is not necessarily a measure of inequality, it does represent how much economic leverage the US has over China. The US is China’s biggest customer by far, and China cannot afford to lose even some of America’s business. On the opposite side of that equation, the cheap manufacturing that China has offered for decades has already begun to shift to other nations who will gladly compete for US business.

A trade war will have costs, but these will mostly land on China, with costs rising exponentially for Chinese manufacturers as the trade war drags on. The costs that impact U.S. consumers will be almost unnoticeable to the average consumer and only severely impact a small set of key manufacturers and commodity exporters. Ultimately, the tariffs could provide a short-term path to a more beneficial long-term trade relationship. Tariffs may be the only viable solution that the US has to solve its trade issues with China.

A Deal Is Only The Beginning

Andrew Middlebrooks and Naufal Sanaullah – EIA Alpha Partners

We have stated our case for optimism on a trade deal with China, which revolves around an analysis of President Trump’s donors, his desire for a deal with North Korea, his relationship with President Xi, the relationship between Chinese Vice Premier Liu He and Western businessmen and political figures, and the underlying policy momentums in both countries. The sequence of events since these notes has reinforced our views, particularly as the Trump-Xi meetings at November’s G20 summit went well, and President Trump delayed his own March 1st trade deadline, which required a deal by then or else the implementation of his threatened 25% tariffs on over $500 billion of Chinese imports (half of which are currently subject to a smaller 10% tariff rate).

Though there are signs of shared corporate interests ultimately resolving the US-China trade spat, tensions remain and are likely to persist across partisan lines. This year may prove to be a decisive one in the crystallization of more aggressive geopolitical strategy with regard to China that spans multiple administrations, transcends administrations, and decenters cooperation over containment, and it will be interesting to see if and how Democrats increase their presence in these debates.

Chinese leadership will be closely following the evolution of the China debate within the Democratic Party, and we will be keeping an eye out for overtures sent by, and nascent relationships being forged by, Chinese policymakers regarding American Democrats. The oppression against Uighur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang province have the potential to be a surprisingly important issue along these lines, as progressive politicians have raised awareness about the abuses. This issue, against the current backdrop of dynamic shifts occurring within the Democratic Party, could end up analogous to the left’s support for Tibetan Buddhist in the 1990s, and drive wedge issues in inter-party debates ahead of primaries.